Bowie's 100 Best Books

Kardamyli

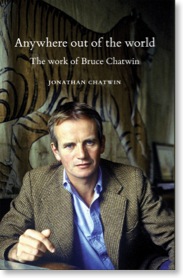

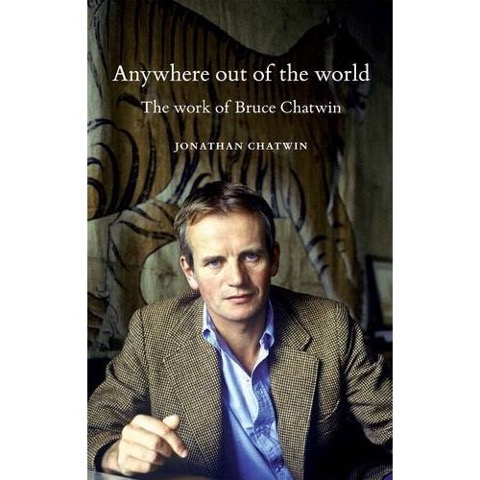

"Anywhere Out of the World" – Now out in Paperback

Writing did not always seem destined to be Bruce Chatwin’s vocation; a sequence of false starts had to be navigated before he eventually settled down to his career. It became, however, the one steady element of a life defined by changes of direction; the only entanglement from which he never turned away.”

From: Anywhere Out of the World: The Work of Bruce Chatwin by Jonathan Chatwin.

'In Anywhere Out of the World Jonathan Chatwin convincingly argues that Chatwin's fascination with the nature of human restlessness is at the core of all his writing as well as his restless lifestyle. [An] intelligent and readable survey ... Jonathan Chatwin's acute probing yields the best account yet of the origins of [Bruce] Chatwin's restless mania.' Nicholas Murray, The TLS, 15th February 2013 Buy in paperback and hardback at Amazon.com Amazon.co.uk Manchester University Press

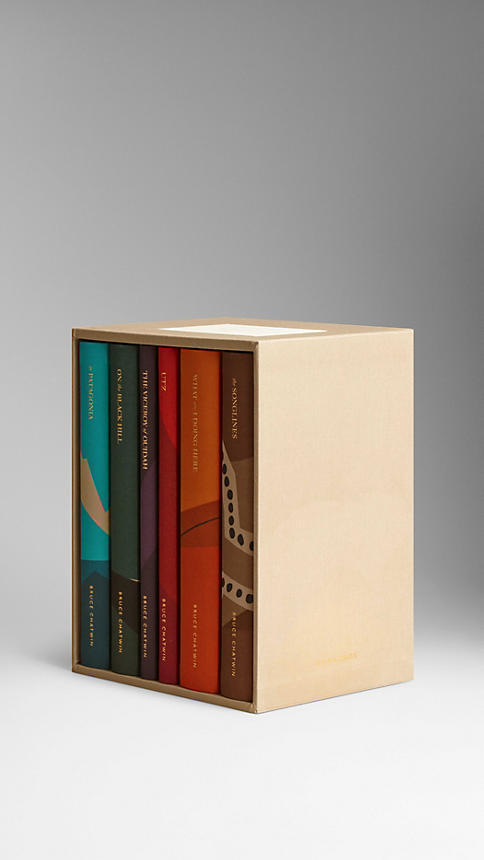

Bruce Chatwin and Burberry 2

Bruce Chatwin & Burberry

Image Credit: Burberry

Blessed Is The Road On Which You Are Travelling Today

"Bruce Chatwin’s memorial service was held on the same day that the fatwa was announced on Salman Rushdie. The moment I read this, I thought there might be a story in it. I liked the idea of one writer’s travels coming to an end just as another was being forced out on the road.

Nicholas Shakespeare’s wonderful biography and the documentary, In the Footsteps of Bruce Chatwin, provided me with some of the details, but I would have to make up the rest. I hoped the tension that would arise between fact and fiction would prove to be an apt means of representing a writer whose books were always difficult to categorise in terms of fiction or travel literature.

The story, Blessed Is The Road On Which You Are Travelling Today, was first published in The London Magazine. I’m delighted that it has now been reproduced here on the Bruce Chatwin website."

'Blessed Is the Road On Which You Are Travelling Today' by Neil Herrington

Tuesday, 14 February 1989

You had never heard of the word until an hour ago, but already your designers are as familiar with the concept as they are with their own mannequins. To your ear, it sounds like the name of a Hong Kong Triad or a term from Jamaican quilting. Not a fat quarter, but a fat-wah.

Since learning the word, you have been unable to get the line of these legs right. Every time you’ve put pen to paper, the pleated skirt in your mind’s eye appears before you on the drawing board like a pair of khaki shorts. Your feet are surrounded by scrunched up sheets of paper. The studio floor looks like the bottom of a hamster’s cage. You rotate the wheel at the side of your drawing board to flatten the angle. Your mind is spinning.

When you started on this outfit, you had imagined it in powder blue, but now you can see that you’re going to have to make it navy. There are two foes doing constant battle within you and, despite your wild flourishes, the businessman in the dark suit usually triumphs over the popinjay in the turquoise cravat. You and your team would not be sitting here today, still hard at work after the events of Black Monday, if navy were not dominant.

Bruce was much the same, except that he claimed it was Cain and Abel who were fighting for dominion over him rather than turquoise and navy: Cain, with the farmhouse in Gloucestershire full of Polynesian spears and fish hooks, lacquerware from Japan and medieval wall-hangings, verses Abel the shepherd, free of possessions, migrating between the plains and high pastures. Bruce was never afraid to alter the facts if they didn’t support the story he wanted to tell. And in the story of his life – perhaps the greatest story he ever created - it was Abel who slew Cain, not the other way around.

Martin brings you your coffee at ten thirty.

‘So what would you do if someone put a fatwa on you?’ he says, settling the cafetiere on the table next to your drawing board.

‘You make it sound like a magic spell, darling.’

Martin has wrapped a blue keffiyeh around his neck. It drapes all of the way to his navel. Lapis lazuli, if not turquoise, is definitely dominant in Martin.

‘I don’t know why we have to honour these people by using their language as if it was our own?’ you say. ‘As if we understand them?’

‘Okay,’ says Martin. ‘So what would you do if someone sentenced you to death?’

‘In absentia?’

‘Yes, you know, like Rushdie.’

‘Well, then I guess I’d become a nomad.’

You last saw Bruce in July, when his brother wheeled him in here, past your design team, right up to your drawing board. All of the boyish mirth had been sucked from his cheeks. He had been in mid-monologue as he trundled through the door, a Bedouin riding a metal camel, his bemused brother, a younger member of the caravan leading him out to his journey into the desert. That irrepressible energy, once transplanted into a sack of bones, made for a deeply disturbing sight - a revolting one, even. You were dubious when you heard at a party during London Fashion Week last year that our eyeballs never grow, that they remain the same size from birth throughout the journey of our lives, right up to the end. But it was so obviously true when you saw Bruce that day. His body was regressing toward the grave and those bulging eyeballs were broadcasting the full horror of the passage: the prospect of his final destination and the despair at all the work he would leave undone.

At first, you didn’t notice the Fortuny dresses he was clutching. You were too busy trying to keep your discomfort at the sight of his emaciation well buried within your own face. That had always been your problem with Bruce - the things he kept buried, the manner in which he curtained off the inhabitants of his various chambers like people inside the changing rooms of a high street store. You were only ever afforded passing glimpses of each other.

He tried to thrust the dresses into your hands, insisting they would help you with the collection you were working on. You were only able to keep from bursting into tears by remaining silent. You took a hold of the handles of his wheelchair, spun him around and pushed him out of the studio, leaving him on the pavement for his brother to collect. That evening, when you were back within the privacy of your own home – a home you had refurbished with him very much in mind, with its bare floorboards, white walls and a framed map of Patagonia in the hall – and had released all of the tears you needed to shed, you wrote him a letter.

You had acted like Cain, you said, wanting to possess him within the confines of that house in Regent’s Park. In time – time he spent wandering without you in Australia – you had learnt to accept that he could only ever live like Abel. It had been a difficult epiphany, but you had reached it and moved on. You didn’t want to see him again.

‘Did you hear me?’ says Martin. ‘Kensington Palace rang earlier. It turns out she’d like to see you at three this afternoon.’

The service starts at half past two.

‘I don’t think that’s going to be possible, I’m afraid.’

‘Oh,’ says Martin. ‘I’ve already confirmed the appointment. There was nothing in the diary.’

‘I’m thinking of maybe going somewhere this afternoon.’

‘Well, can’t it wait?’

You place your pen on your drawing board’s parallel motion rule - rather more firmly than you intend - and swivel around to face him.

‘No, Martin, it cannot.’

‘But, how can I…’

‘Just tell Her Highness I’m ill or something. For God’s sake, darling, that’s what I pay you for.’

Martin throws his keffiyeh over his shoulder, turns and walks away.

‘And anyway, Martin, how on earth could you possibly greet the Princess of Wales dressed like that?’ you shout after him.

You head into Soho for lunch and push penne around your bowl in Da Aldo. You cannot imagine creating anything of worth if you return to work. Without thoughts of food or fashion filling your mind, you start to feel as if one of your seamstresses is unstitching the very fabric of your being.

When you return to Great Marlborough Street, your legs take you straight past the studio and on past Liberty. You forget to inspect their new window display and find yourself ensnared by the torrent of shoppers gushing down Regent Street. You thrash your way across like a man lost overboard trying to swim to the riverbank. You wash up in Mayfair and head down Maddox Street in a daze. You usually feel a tug of curiosity when you peer down Mill Street at the entrance to Savile Row, but today it’s not even strong enough to make you contemplate your own suit in the window of The Mason’s Arms. It’s only when you reach New Bond Street that you start to think about your immediate surroundings. You can see the awning protruding from the front of Sotheby’s. You did not know him when he worked there, but you’ve seen the photos. He was always a boy to you, despite being twenty years your senior, but he really looked like a boy in those pictures, standing among the elderly men of the antiquities department. You often wonder how someone like you could have fallen in love with a man who, in his forties, still dressed like a cub scout.

Maddox Street becomes Grosvenor Street and you realise you’re approaching the American Embassy. His wife is American. She will be there of course. You don’t know why you’re still walking. Why do you keep forgetting that you don’t owe him anything? You should just hail a cab. He may have liked to claim that he walked everywhere – you know that he didn’t, because you paid for the taxis - but that doesn’t mean you have to walk towards him this final time. Long before today, you figured out that his wanderlust was nothing more profound than a means of staying beyond the confines of your house in Regent’s Park or his marital home in Gloucestershire. You wonder where all the damn taxis are. Maybe that was unfair. Perhaps his life was a quest to try and understand the peculiar and the extraordinary – nomads, Patagonia, Songlines. But if it was, then it was only as a means of contextualising his own extremes. If he could prove that the world was full of exceptions, then maybe he might be able to normalise his sexuality. Why are you going over all of this again? You thought it was all dead and buried. You don’t know why you are doing this, but here comes a cab.

‘So what do you make of all this nonsense about salmon rösti?’ says the cab driver as you head up Park Lane.

‘Does salmon rösti actually exist?’ you say. ‘I didn’t think the Swiss liked mixing cheese and fish’.

Your mind immediately travels to Oxford and to Bruce holed up in The Churchill Hospital, not long after his collapse in Zurich. That was when he told you he thought you ought to have a blood test.

‘I’ve just bought a copy of the book,’ says the cabby, holding up a hardback edition of The Satanic Verses. ‘Can’t make head nor tail of even the first page. It seems like two blokes are falling out of the sky, but I’m not sure. God knows what all the fuss is about.’

‘Ah, yes, of course,’ you say, leaning back in your seat. You try to think instead of Bruce in Bali and Venice: flashes of revelation; snatches of contentment. But both trips ended with him boarding a plane somewhere by himself, off on another quest; one that ultimately led back to his wife.

A couple of photographers are loitering on the steps as you pull up outside the church. You wonder if the books or the disease have brought them here. You fear it may be the latter and have no desire to be associated with it any more than Bruce did.

‘Do you mind going round the block?’ you say to the cabby. ‘I’m a bit early.’

By the time he has driven to the end of Moscow Road, down to Notting Hill Gate and back up again, you are running late and the photographers are still there. You consider pulling up your collar and ducking through the doors, but don’t wish to appear in tomorrow’s papers looking ashamed. You could of course ask the cabby to drive on, but instead you pay him and step out of the taxi with your head held high. Neither photographer bothers to look at you, let alone take your picture, as you step into the church.

An enormous cross dangles from the apex of the dome above the altar. As you make your way through thick incense smoke towards an empty pew, another dimension comes into view and you realise the cross is in fact a giant jack. You appreciate the designer’s intentions, but the overall effect rather infantilises the symbolism.

The church is small and the turn out strong. You can discern clear groups: the old effeminates of Sotheby’s; booze-blemished hacks; writers and travellers. Your mother is sitting with Bruce’s widow in the family section. You remember a friend’s mother once telling her boyfriend that she’d destroy him if he ever broke her daughter’s heart. That’s the way it’s supposed to be, apparently. But your mother invited the man who broke your heart to go and die in her house in the South of France. She didn’t tell him to fuck off and die. No, she turned her house into a hospice for him. She said he was irresistible, as if you were unaware of that fact. She said his suffering released a flood of compassion within her. You have no reason to disbelieve her, but it surprised you that his suffering was powerful enough to blind her to yours. Perhaps the bond between writers is greater than that between mothers and sons. Maybe it was easier for her to relate to Bruce - furiously scribbling his way unto the end, fighting the same impotent battle against the long night that all writers fight - than to you. It doesn’t upset you. You’re just curious, because you weren’t drawn to fashion in order to try and outlive your mortal bones. The odd silken robe is unearthed from ancient Chinese tombs from time to time; you and Bruce both considered the toga to be an elegant and relevant garment for the modern day as well as ancient Rome; but no one should go into fashion in a bid to cheat death. No, nobody should go into fashion for any reason other than the damn frocks. It’s transitory, fickle and more than anything, it’s a bloody business.

You take a seat at the back, among the writers. You know they are writers because some of them are trying not to laugh. They spend their days alone at their desks, creating imaginary universes and living as gods within them. You suppose they are unable to countenance the fact that today they are guests within the house of another deity. That or they are just glad the competition has receded a little. God, you can see the urn from here, resting on a little wooden table in front of the altar. You’d heard he’d been cremated in France last month, but had no idea that Elizabeth would bring the bloody ashes with her.

An Indian man rushes in with a woman and they sit in the pew in front. He looks as if he left the house with a full head of hair, neatly parted at the side, and it has moulted on his journey here until only a threadbare gauze remains coaxed across his scalp. If you were him, you would crop it much shorter. The snarly-faced writer sitting next to him leans over, places a hand on his shoulder and whispers something earnestly, but the Indian man is elsewhere, oblivious. You too feel unsettled. You thought you had been close to Bruce not so long ago, but the only people you really know here are his widow and your mother. It’s as if not only the changing room curtains have been drawn back but the walls to the store knocked down as well. Suddenly, you the people in Bruce’s life, the people whom he fought so hard to keep apart, are all confronted with one another. You wonder who here even knew he’d been in the process of converting to Greek Orthodoxy on his deathbed. You certainly didn’t.

After the priest has intoned the words ‘blessed is the road on which you are travelling today,’ he doesn’t speak another word of English, save for Bruce’s name. You doubt that anyone else here speaks or understands Greek - not even the man inside the urn. The writers snigger every time the sound Bruuuce emerges from the Hellenic incantations, all except the Indian man who is anywhere but here. Words are important to them and they don’t know how to behave when the tools of their trade are rendered meaningless. If only they opened their eyes, they’d see the elegant simplicity of the priest’s black cassock and the ornate extravagance of the cross that hangs around his neck. You could gaze at this old man’s celestial beard for hours and feel content to follow him as he leads you in standing, sitting, kneeling then sitting again. You’re very thankful that the ceremony is being conducted in Greek. You don’t want to be told who Bruce the public writer was or what you should think of him. You know what you think of him, although you could never express it in words any more comprehensible than the sounds emanating from this priest’s mouth. The main part of Bruce’s magnetism lay in trying to figure out who the hell he was. You don’t want any help with that.

You first met in Greece and are surprised that he is destined to return there to rest. There was nothing restful about that evening at the restaurant by the port. You were with a girlfriend and he with a group of men. It was loud and boozy and, as much as you hope Bruce finds peace overlooking the Messenian Gulf, it is eerie to think that his excitable voice will never again grace a gathering of friends at an al fresco supper. You spoke a bit that night, but it wasn’t until you had both returned to London and he called you up to invite you to lunch at his flat that you really started talking. You knew you were beyond help even before you rang the buzzer to his building that first afternoon - he had certainly deduced it. There were moments when you wished he would stop talking, when you’d had enough of being entertained, but they only lasted for a few minutes. Now, five books are all you have to fill the silence he leaves behind. He did have a tendency to repeat himself, but still, the prospect of re-reading those five books over and over again seems rather pathetic, especially when you consider the length of the ensuing silence.

Some latecomers have arrived and are shuffling closer to your pew. Although there is space beside you, they make no effort to sit down. One of the latecomers – a woman with what appears to be a dictaphone in her hand – is wearing the most beautiful pair of tailored trousers, with thick turn-ups and chunky belt loops. You realise this is exactly what you were trying to draw this morning. You remove a sketchbook from your inside pocket in order to capture these particular features. You don’t want to impose khaki shorts upon the high street, but you do want to reinvigorate the turn-up. When you finish the sketch, you flick through the other pages and look at ideas for necklines and some earlier drawings you made during a New Year’s party in Tuscany. Beneath some studies of renaissance doorways, you discover four lines of verse you have no memory of writing, although the hand is definitely yours:

You’re not a nomad but a rover,

Unwritten book upon your shoulder,

Where are you really going? Always home,

What other reason’s there to roam?

The writer next to you begins to chuckle harder and you snap shut your sketchbook. He is wearing big round glasses. As the service draws to an end, he leans forward and taps the balding Indian man on the shoulder.

‘Well, Salman, I suppose we’ll all be back here for you next week,’ he says and you finally realise who the balding Indian man is. Bruce had mentioned his plans to meet Rushdie in Australia when he was researching The Songlines, but you never got to hear whether they came to pass.

The latecomers begin to congregate more closely at the end of Rushdie’s pew, as if they were only able to acknowledge his presence upon hearing someone speak his name, despite the fact that they could all have seen him from where they were standing. For he spoke and it came to be. You notice they are all holding dictaphones or notebooks. The snarly-faced writer and Rushdie’s female companion try to lean over and push them back and it looks as if things are about to unravel.

Rushdie stands to leave, but he is not very tall and is soon swallowed up by the burgeoning press pack, who assault him with questions. You hear his plea that today is about Bruce, not him, but he must sense this is no longer true. As his threadbare crown is obscured by the journalists, you wonder who is more dangerous: they or the Islamists. The thought occurs to you that an Islamist could very easily be hidden among their number and you wonder if all of you in the congregation are perhaps in danger. You consider making an undignified dash for the exit, then remember how some people would fear catching Bruce’s illness just from being in his presence. You don’t really understand what Rushdie has done, but you’re sure he doesn’t deserve to be treated in the same manner that Bruce was. Ever since the news broke, you have worried that the word AIDS will obliterate Bruce’s books; Rushdie’s work must also face a similar threat from this new word, fatwa. You wonder if Bruce would be pleased or insulted that his memorial is turning into an international media event stretching from Bayswater to Tehran and beyond. Your guess is that he would dine out on the story for weeks if only he were able. When artists die young, it often seems like a drink or drug-fuelled inevitability - a merciful blessing in many cases - but Bruce had only just got started, really. There was so much about which he was still curious.

You manage to inch past the press pack and back down the aisle of this magnificent church, glad that Bruce is still trying to impose his style and substance upon you right until the bitter end. The sky is overcast, yet you are blinded by a murky light when you leave the church. Photographers are lining the steps, ready to snap you as you leave, although you now understand that they have no idea who you are. Were an Asian man other than Rushdie to leave the memorial before him, you sense the photographers would unknowingly expend their reels of film on the poor chap.

‘I’m glad you decided to come,’ says a croaky East Coast voice.

You turn around and gaze into the open eyes of Elizabeth. She is clutching the urn. It occurs to you that this is the only time she has ever truly possessed him and you’re relieved to discover you don’t resent her for it.

‘I wasn’t sure I wanted to,’ you say. ‘But I’ve been thinking about nothing else today. I figured I may as well be here.’

‘I’m pleased. And so would he be,’ she says, tapping the urn.

She has never carried any malice for you. She is unflappable, which you now realise makes her far better placed to have been Bruce’s companion than you.

Rushdie emerges from the church to an explosion of camera flashbulbs. The press pack chase him and his pathetic literary bodyguards down the steps and along the pavement, the sheep, the shepherds and the predator seemingly moving as one. He is not yet a man on the run, but he shall have to get going if he wants to survive the day.

‘We should be good at this,’ says Elizabeth, when the Rushdie entourage has disappeared from sight. ‘I mean, if loving Bruce taught us anything, it was how to say goodbye.’

You were feeling better, but are on the verge again.

‘I hear you’re taking him to Greece,’ you say, regaining control.

‘There’s this ruined Byzantine church he liked to visit when he was finishing The Songlines. We fly tomorrow.’

‘His final journey,’ you say and think how appropriate it is that the end of Bruce’s travels has coincided with the beginning of Rushdie’s inevitable flight into exile, as if Bruce has passed on an invisible baton. ‘I like what the priest said at the start.’

‘Blessed is the road on which you are travelling today.’

‘Exactly,’ you say, wrapping your hands around hers, still clutching the urn. You try to think of something else to say and are sure she understands this as you turn and walk away.

Remembering Bruce Chatwin

In the last twelve years of his life, he produced five astonishing and original works which continue to resonate with readers today, as this weekend's commemoration at Chatwin's alma mater, Marlborough College, proved. Sixth Form students had been reading and discussing his work in the preceding weeks, and were articulate and interested in the responses to talks by myself, Susannah Clapp and Nicholas Murray. One, in response to my query as to whether she believed literally in Chatwin's theory that humans are predisposed to a life of travel, told me: 'No. But I'd like to.'

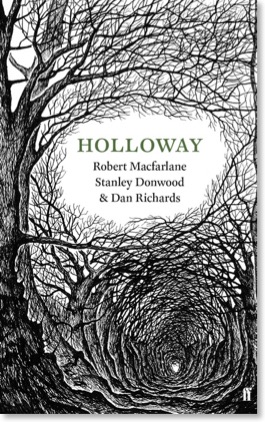

Books about walking

Meanwhile, in the Guardian, William Dalrymple reviews Macfarlane's new, slight volume Holloway. Written with friend and fellow-traveller Dan Richards, and illustrated by Stanley Donwood, Holloway is 'an exceptionally written, gorgeously produced little gem'.

Recap

A few things to catch up on, then:

i. The Australian has a fascinating piece on the relationship between D.H. Lawrence's Antipodean novel Kangaroo and Chatwin's The Songlines. Chatwin read Kangaroo whilst researching his own work, and there are some similarities – not least the fact that both cleave closely to the lived experience of their respective authors whilst in Australia. The assessment in The Australian, somewhat unusually for an establishment from that part of the world, praises Chatwin's work for the manner in which its author was able to see beyond the narrow concerns of those writers and anthropologists more deeply involved with the world described:

"Again, there is in his case the capacity of the outsider to think things that hover almost beyond the range of the local writerly elite, or beyond the scope of what they are prepared to say. Chatwin was the ultimate jaded connoisseur of used-up Europe, the traveller in search of some new language. Above all he wanted a fresh kind of silence, not the overloaded silence of the funerary smoke draped over the old continent. He was in rebellion against standard, sequential forms of narrative: his instincts pushed him towards a landscape that lent itself to portrayal in fragments, in rhymes and patterns and reduplications."

ii. From last month's That's Beijing comes a Chatwin-related interview with yours truly. This was in anticipation of a session at the Beijing Capital Literary Festival, with myself and the New Yorker journalist Evan Osnos, which happened on March 11th, and which should be available soon as a podcast.

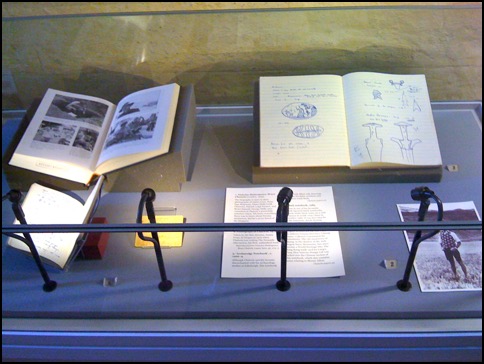

iii. Finally, the Guardian has an article regarding the upcoming stock market flotation of the company that make Moleskine notebooks – created in the image of Chatwin's description in The Songlines of the unbranded notebooks that he used for much of his writing life. The potential valuation is an astonishing 600 million Euro.

The NYTimes does Patagonia

'Since Bruce Chatwin’s days, the world has gotten much smaller and more familiar, and yet Patagonia retains an anachronistic feeling of being truly far away.'

One wonders, in these days of luxury resorts and plane-chartering, how much longer this will be the case.

Read the full article here.

Image: PerfÃdia

Self-Promotion PT2

Off the beaten track

"Many bestselling and award-winning travel writers have turned out to be distinctly unreliable narrators. Should we file their books under fact - or fiction? And do readers really care?

Made-up characters, placing themselves in the thick of it when they were not actually there, embroidering reality - these are just some of the charges that have been made against writers including Patrick Leigh Fermor, Norman Lewis, and Bruce Chatwin since their deaths."

There are no surprises, but it nonetheless goes to show that – more than thirty years after In Patagonia – no real consensus has been reached over what the incumbent responsibilities are of those who write of travel.

PLF

Kevin Rushby goes travelling in search of them both in the Guardian.

Meanwhile, the Wall Street Journal goes more in-depth, looking back in detail at Leigh Fermor's life. (There's also a nice slideshow, with interior and exterior shots of his beautiful house, now bequeathed to the Benaki Museum).

Self-promotion

On a different note, it's recently come to my attention that there's a good Facebook source of news on Chatwin titled Bruce Chatwin's Notebook; do go and check it out. Of course, it's also possible to keep up to date via the brucechatwin.co.uk Twitter feed at twitter.com/chatwinnews (or you can simply search for the handle @chatwinnews).

'The Songlines': A Penguin Classic

'In his facts and in his fiction (he once observed that he didn’t think there was a distinction), the world is intricate but not opaque. Everything, from Aboriginal myths to childhood memories and adult encounters, is fixed, placed, and overdetermined. The connections between his darting brief images may be omitted, but they are not ambiguous, and the reader can only draw one conclusion from his parables.'

At present – and this is true of the Penguin In Patagonia – this edition of the The Songlines is a Penguin U.S. publication, which seems both surprising and disappointing given Chatwin's nationality.

'It's marketing, not science.'

More on the floatation from Reuters here.

Notebooks and other items from Bruce Chatwin's archive on display at the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

'In Patagonia': Robert Macfarlane's Book of a Lifetime

'What I learnt above all from Chatwin is that travel writing – unpropelled by any narrative except the journey itself – must find alternative momentums. He taught me that pattern can substitute powerfully for plot: that apparently unconnected details and images, sprinkled as iron filings through a book, might be magnetised into subtle arrangement.'

Macfarlane's new book – partly inspired by Chatwin, and receiving rave reviews – is The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot.

'The worst thing is choice'

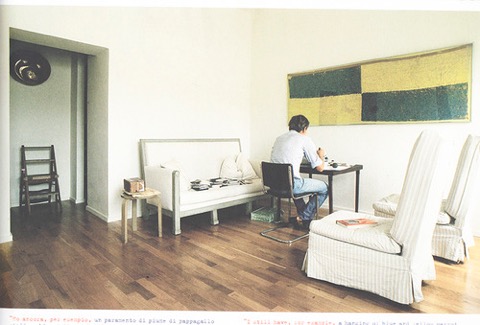

'He wanted to travel light. But of course in his apartment he had a lot of things.'

Baronessa Beatrice Monti della Corte

'Bruce Chatwin gave me the idea, without either of us really realizing it. He used to visit Santa Maddalena to write.

When my husband died, I realized I still wanted my house to be a place where writers like Bruce could come and work. For the first year I invited my friends, simply because it was the easiest thing to do. And it grew from there.'

Amongst other prominent writers, she has hosted celebrated figures such as Orhan Pamuk, Michael Cunningham, Edmund White, and Zadie Smith.

La Legge dell'odio

My Italian isn't what it should be, but it appears that journalist Alberto Garlini has written a long novel which features a central protagonist based on Chatwin. The finer details escape me, but Garlini said of the book: "I wanted to write a novel about Bruce Chatwin with a cameo of a fascist, and I wrote a novel about a Fascist with a cameo of Chatwin."

You can buy the Kindle edition here and read more of the interview with Garlini here. I'd be interested to hear from anyone who has more details on the novel: please do get in touch.

Peter Whitfield: 'Travel: A Literary History'

'It’s often said that since we can all travel anywhere, what’s the point of travel writing? But I think that in a world where so much is phony, we need to find the genuine, and this is what the travel writer is for now: to show us what’s under the surface; to warn us what tourism does to us and to the places we visit.'

Find more here.

In the footsteps….

Bruce Chatwin 'saved' travel writing

Saved travel writing by changing its mandate: After Chatwin, the challenge was to find not originality of destination but originality of form.

Among those who have followed Chatwin, the most interesting have forged new forms specific to their chosen subjects: thus Pico Iyer’s sparkily hyperconnective studies of globalized culture and William Least Heat-Moon’s “deep maps” of America’s lost regions. Perhaps most important were W.G. Sebald’s enigmatic “prose fictions”—particularly “Rings Of Saturn”—that likewise hover between genres, make play with unreliability, and fold in on other forms: traveler’s tale, antiquarian digression, and memoir. What Sebald, like so many of us, learned from Chatwin was that the travelogue could voyage deeply in time rather than widely in space, and that the interior it explored need not be the heart of a place but the mind of the traveler.

You can find the full article – behind a firewall – here.

Hat-tip: worldhum.com

Macfarlane's new book The Old Ways – partially inspired by Chatwin – is out in June.

Patagonia

'It was always about the people. I never spent days waiting for the right light by a lake. It was never my idea to shoot pretty sunsets. My idea was to shoot the people in relation to the landscape.'

A Card from Angela Carter

'A very unlikely card, in a way, for Angela to send, is the Maori creation myth card. It’s not the kind of thing you’d expect her to be interested in. Her interest in mythology and fairy tale and the landscape of the unconscious was very different to that sort of overarching myth. She was much more drawn to individual mythologies, to Kleinian and Freudian explanations, and to fairy tales, which have a more precise and personal narrative.

I have a feeling that there’s a sort of half-joke at Bruce Chatwin’s expense in that choice of card. Angela would have known that some of the more extravagant claims that Bruce was making in The Songlines, about the origins of the unconscious, were not, perhaps, absolutely anthropologically accurate.'

The book is also well worth a read.

Birds of Paradise

‘Chatwin remains like a showy bird of paradise amid the sparrows of the present English literary scene, and it is impossible to reread In Patagonia without a deep stab of sadness that we have lost the brightest and most profound writer of his generation.’

Sabbatical

The major news in the intervening weeks has been the death of Patrick Leigh Fermor, Chatwin’s great friend and mentor.

There have been a number of pieces written on Leigh Fermor; perhaps the pick of them are these three:

Jan Morris in the Guardian

William Dalrymple in The Daily Beast

Christopher Hitchens in Slate

Most express a sentiment which I share – that we shall not see his like again.

Huffington Post

Nicholas Shakespeare on Benin

Under the Sun in America

“One of the pleasures of a good book of letters is watching a voice develop and ripen over time, and Chatwin’s does. It grows lovelier, grainier, more confident, more wicked.”

The New York Times

“Chatwin's real subject, however, was not nomadism but himself.”

Washington Post

A “jumble-box of arcana”.

Wall Street Journal

“His letters, alas, reflect little of this charming writer's soul. They are, in fact, among the least revealing of authors' letters that I've ever read, which surely must have been intentional on Chatwin's part. They are frustratingly superficial.”

Chicago Tribune

“Readers of the biography will be familiar with much of it, but addicts will want it all.”

Salon

“This 500-page selection of the writer’s letters provides not revelation but evasion; not features but a mask. Except that evasion is heart’s blood; the mask, his countenance.”

Boston Globe

On the Black Hill

Why not at Ryman's?

Book of the Year

Under the Sun Pt. 5

“The one thing you might have thought that none of us really needed was yet another Chatwin book: least of all 550 pages of his letters. Yet the letters are wonderful, and while they do give much ammunition to those who want to dismiss Chatwin as a social-climbing show-off, they contain many intriguing insights into his life and writing. Moreover, they are the closest we are ever going to get to a Chatwin autobiography.”

A more equivocal appraisal from Nicolas Rothwell in The Australian.

And Nicholas Murray’s always-worth-reading view at his blog.

Interview with Elizabeth Chatwin

An interesting chat with Elizabeth Chatwin which I only recently discovered online, and which is well worth a view.

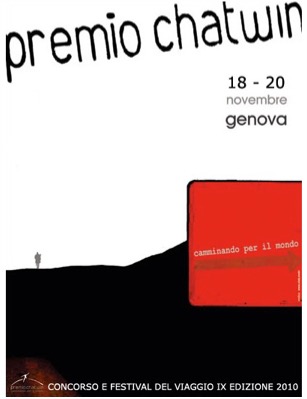

Premio Chatwin

Some of you may know that the Europeans put Chatwin’s fellow countrymen to shame when it comes to demonstrating their appreciation of Bruce’s work. The Italians, in particular, consider Chatwin something of a god, and have, for a number of years, organised a festival and prize in his honour. It is called the Premio Chatwin and it is happening this year between the 18th and 20th of November in Genova.

An article from Blue Magazine, kindly supplied by the translator Sheila Oppezzi, explains more:

Premio Chatwin

Spoken too soon

A Guardian review simply isn’t enough; the Observer want to have their say too.

I’m also going to point interested readers in the direction of Hugh Thomson’s website thewhiterock.co.uk, where you’ll find not only a blog post on the Letters from the man who reviewed them for the Independent, but also a whole host of other pieces of interest.

Under the Sun Pt. 4

And that, I imagine, will be that until the US version is published early next year.

Under the Sun Press Pt. 3

The Independent

Blake Morrison asks ‘Does anyone read Bruce Chatwin anymore?’ in The Guardian

The New Statesman

A blog review by Adrian Slatcher.

And finally Literary Review.

Your View on Under the Sun

Under the Sun Press - Theroux Special Edition

‘While he was alive, I teased him and questioned his unreliable accounts of travel. His death was a shock and when he was more or less beatified by the critics, I rolled my eyes. But with each passing year I am more convinced that he was the real thing, an original in all his work, and Rimbaudesque in acting on his belief that life is elsewhere.’

You can read the whole piece here.

Under the Sun Press Pt. 2

A sympathetic and interesting interview with Elizabeth Chatwin in today’s Telegraph.

A typically insightful review in the Spectator by Philip Hensher.

And finally, a gossipy column from the Evening Standard, which manages to avoid any mention of Bruce’s writing.

More as I have it.

Under the Sun Press Pt. 1

The first drips of what will surely become a flood of publicity for Under the Sun: The Letters of Bruce Chatwin are beginning to fall.

Nicholas Shakespeare writes a typically eloquent piece recounting his journey to Athos in search of the rusted metal cross which inspired Chatwin’s conversion to the Orthodox faith:

‘One afternoon after his usual maté (mistaken by the cook for hashish), Chatwin walked to the monastery of Stavronikita, once painted by Edward Lear. He puffed towards it with his heavy rucksack. “The most beautiful sight of all was an iron cross on a rock by the sea,” he wrote. From where he stood – just below the monastery – the black cross appeared to be striving up against the white foam.

Then these words: “There must be a god.”’

Another more perfunctory - though positive - review of the book from the Irish Times can be find here.

I’ll be posting articles here as they come through, but please feel free to forward any you think I might have missed using the contact form.

Under the Sun: The Letters of Bruce Chatwin is published by Jonathan Cape, and will be released in the UK on September 1st 2010.

BBC Four

Journey to Chora

“In November 2008, I travelled to the Mani in Greece to visit the tiny ruined chapel of St. Nicholas in Chora, “a tenth century Byzantine church on a headland two miles up a mountain,” as described by Patrick Leigh Fermor in Nicholas Shakespeare’s biography of Bruce Chatwin. More specifically, I was making my way to an olive tree very close to the church under which Elizabeth Chatwin had elected to bury the ashes of the writer, her late husband. He came to know the chapel when he stayed in a small apartment at the Hotel Theano in nearby Kardamyli for seven months writing the first draft of his book The Songlines. The ancient church had been one of his favourite places.”

View the whole essay here.

The Morality of Things

Here lies the power of objects providing intimations of immortality disguising loss under a veneer of eternal value. Of course, there is something ironic in the fact that most objects will survive its owner, from gold rings, to a pair boots, or even a 2-cent plastic non-biodegradable supermarket bag. Chatwin also wrote: “I have often noticed that in the really great collections the best objects congregate like a host of guardians angels around the bed, and the bed itself is pitifully narrow. The true collector houses a corps of inanimate lovers...”’

Hat Tip: Buenos Aires Herald

Dan Franklin

"We now go to Pizza Express over the road. The publisher's lunch was really dying out anyway. Tony Whittome from Hutchinson retired recently; he'd been there 40 years and he did the lunches with Kingsley Amis. Two malt whiskies when you sat down, two bottles of claret and then calvados, but people don't really do it any more."

More at The Guardian.

BODcast

The Kapuściński Case

The full piece here.

For those of you unfamiiar with the story, illumination can be found here.

At the Bright Hem of God

The Future of Travel Writing?

"Last year, on a visit to the Mani in the Peloponnese, I went to visit the headland where Bruce Chatwin had asked for his ashes to be scattered.

The hillside chapel where Chatwin's widow, Elizabeth, brought his urn lies in rocky fields near the village of Exchori, high above the bay of Kardamyli. It has a domed, red-tiled roof and round arcaded windows built from stone the colour of haloumi cheese. Inside are faded and flaking Byzantine frescoes of mounted warrior saints, lances held aloft.

The sun was sinking over the Taygetus, and there was a warm smell of wild rosemary and cypress resin in the air. It was, I thought, a perfect place for anyone to rest at the end of their travels.

My companion for the visit was Chatwin's great friend and sometime mentor, Patrick Leigh Fermor, who was Chatwin's only real rival as the greatest prose stylist of modern travel writing. Leigh Fermor's two sublime masterpieces, A Time to Keep Silence and A Time of Gifts, are among the most beautifully written books of travel of any period, and it was really he who created the persona of the bookish wanderer, later adopted by Chatwin: the footloose scholar in the wilds, scrambling through remote mountains, a knapsack full of good books on his shoulder.

Inevitably, it was a melancholy visit."

Japanese Influences

‘Some Japanese influences on style and structure in Bruce Chatwin’s writing.’

Further Responses to Patagonia - A Cultural History

Patagonia - A Cultural History

“[W]here the book is at its brilliant best is in its unfailingly perceptive analysis of those who have interpreted Patagonia, from the 19th-century ornithologist WH Hudson (one of Britain’s greatest nature writers) to the French philosopher Baudrillard. Moss rightly points to the sheer mediocrity of recent British travel writing on Chile and Argentina; but he is also critical of such hallowed names as Chatwin (“dated and dusty”) and the ever tetchy Paul Theroux, whose failure properly to engage with the region’s unpopulated expanses is perhaps indicative of his fundamental superficiality as an author.”

Articles of Interest

“I have this postcard of a Tiepolo ceiling in Wurzburg, that I was sent in 1987 by the late travel writer Bruce Chatwin, whose biography I wrote. He had driven to Prague in his 2CV with his wife Elizabeth in order to gather more material for his last novel, Utz. His German publisher who saw the Chatwins at this time had the idea that "after all the battle of life they would be together ..." I had the impression of a wonderful couple like Ovid's Philomen and Baucis.” See the card itself here.

Another relevant piece of news in this morning’s Guardian, namely an interview with Francis Wyndham, who was both a great friend and something of a mentor to Chatwin. Asked about what sort of person Chatwin was, Wyndham responds in glowing terms:

'I absolutely loved him. I found him life-enhancing. You wouldn't see him for ages, then he would just turn up. He was a bit like Jean [Rhys]; he would talk about what he wanted to talk about. It was a monologue, but it was a monologue that I wanted to hear.'

Finally, continuing a series of programmes on travellers of the twentieth century, Benedict Allen presents a documentary on the life of another great friend of Chatwin’s, Patrick Leigh Fermor. The programme is well worth watching in its entirety, but Allen does discuss Chatwin at some length towards the end of the show. It has passed by on mainstream television, but can be found for two more days on BBC iPlayer.

Bruce Chatwin Conference

From WorldHum.com 'In Patagonia, In Patagonia' by Tim Patterson

The fleece from an ex-girlfriend. The windbreaker I found secondhand. The ski pants I “borrowed” from my college roommate. The thermal underwear from Santa. The socks I treated myself to after three days of biking through the Chic Choc mountains in the rain.

Even my daypack is a Patagonia One Bag, with sealed zippers and a pocket that fits my laptop like a men’s R3 glove.

All well and good. Patagonia makes fine gear that blends form, function, corporate ethics and mountaineering chic.

But I wasn’t bound for the Rockies or the Alps. I was headed to the Andes. Patagonia—for six months. And here I was, looking as if I had just stepped out of a Patagonia catalog.

Como se dice ”tacky gringo”?

The Patagonia brand doesn’t distort Patagonia the place so much as it appropriates its image as a marketing tool, distilling stark mountains and outlaws and barren windy plains into a vague perfume of mystic coolness that makes yippies (yuppy-hippies like me) reach for our MasterCards.

Google “Patagonia” and the first result links not to a site about the place, but to the company site, where you can purchase jackets, shirts and footwear.

In the brave new world of a California-based search and technology information company, a California brand takes precedence over a place that is half the size of California.

As my red-eye to Buenos Aires taxied down the runway at JFK, I popped a sleeping pill and balled up my Patagonia fleece into a makeshift pillow. Just before passing out, a thought crossed my mind.

Was my trip nothing more than a logical extension of my brand identity? Did I buy my air ticket to the end of the Earth in the same way I might click on a text-link ad specifically targeted to my interests?

Was I following in the footsteps of Bruce Chatwin, or was I in Patagonia to make a fashion statement on a continental scale?

See here for the full piece.

Granta celebrates 100th issue

New Look

The Bookseller

'Vintage Books has repackaged the backlist of travel writer Bruce Chatwin in a bid to bring his books to a new generation of readers. The new books will all have striped covers in vivid colours, which "represent images and themes within the books," the publisher said. The black and white bars across The Viceroy of Ouidah represent the slave trade, while the colourful stripes on Utz recall a Meissen harlequin (the protagonist is a devoted collector of Meissen porcelain); the stripes on In Patagonia, On the Black Hill and Songlines are designed to reflect the landscapes described in the books. "This stylish, elegant re-design is intended to bring the much-loved and admired Chatwin to a younger audience and also highlight the sophistication and vivid nature of his work," the publisher said RH designer Michael Salu added that the covers are "an exercise in the evocation of a time, place or emotion through the most basic application of colour and shape. They are a riposte to the culture of decadence prevalent within much visual communication." The move comes in line with plans by the imprint—which is part of Random House's CCV division—to move into classics territory with the launch of a new list, Vintage Classics, to house out-of-copyright works.'

On the Black Hill on Stage

Taken from the Western Mail, October 19th 2007; review by David Adams.

'BRUCE CHATWIN’S marvellous novel, set just outside Abergavenny, has proved to be a minor classic. Andrew Grieve’s film of the book was vivid and much admired and Charles Way’s stage adaptation for the Made in Wales Stage Company, was one of that company’s finest hours. Now Way, a quarter-of-a-century on, has adapted it again for the ajtc Theatre Company and Guildford Yvonne Arnauld Theatre. How times have changed during that time is evident, not so much in the script but in the form – a play that had a cast of 12 is now a two-hander plus accompanying cellist.

Way was in many ways the ideal writer to adapt On The Black Hill. Not only is his home in Abergavenny, but his plays take that same long view, seeing a world of change in the lives of a few.

And Gwent Theatre’s small space in Abergavenny, the Melville Theatre, was the perfect place to catch the show on its UK tour.

I think this pared-down version, where that broad sweep is seen through the eyes of the two twins, could have worked. It is their relationship, their honest, uncluttered views, their unambitious coping with the vagaries of life, that is at the heart. But Iain Armstrong and Mick Jasper, while clearly committed, just don’t capture the essence in any way, rarely escaping their very Englishness, their simple cloth clothes and bare feet hinting at a dated pseudo-classic poor theatre, their scampering style at odds with the tenor of the narrative.

There is the inevitable accent problem – that border one isn’t easy to catch, but we are expected to accept here that two twins seem to come from two different parts of Wales.

But it isn’t just that, or the sub-Dylan Thomas- esque comedy of some scenes, or the difficulty of the actors playing the joint narrators, the two central characters and their parents and neighbours, including mother, sister and girlfriend.

It’s that the performance in general just doesn’t grab you, rarely moves you, and quite certainly doesn’t have the epic scope of the book or the original play. The short scenes and exaggerated playing of so many characters look like a cut-down comic-book version of a classic.

And the cello in the corner? Lewis Gibson’s music (performed by Harriet Bennett) was predictable and unnecessary – the Black Hill is raw and earthy, and the choice of a cellist rather than an actor who might have played the women in the story does, sadly, seem typical of a production that is far too fey.'